The Traveler’s Dilemma is a generalization of the Prisoner’s Dilemma.

The starting point of the problem is the following one: two people have lost identical baggage, and the airline company offers them a monetary compensation.

This two individuals have to tell the company which is the value of the lost baggage, and the company will pay the lowest of the two mentioned values… with an extra complication: the humblest one will receive an extra compensation of , and the most ambitious will receive the stated value minus .

There are many variations of this problem, but we’ll use a prices range between and (both included), the prize for being humble will be , and the punishment for being too ambitious will be instead of

(I did some computations and I don’t want to repeat them with more “standard” parameters).

The main interesting point of this dilemma is that, if we apply naive “rationality”, we fall in “prices war”: I start with as a good starting point, and then I think that if I choose , then I could win , but probably my oponent will think the same way, so maybe choosing is a better option, because then I can win instead of , but my oponent will think the same way… and if we continue thinking, we’ll eventually reach a proposal of or …

Alternative rationality

Of course, real people aren’t so “rational”, and tend to propose higher prices than the lower bound. There are many theories about why people are “irrational”, and of course many of these theories also try to improve our insight on the strategies used in this sort of games ¹ ².

Personally, I don’t like tagging as “irrational” some strategies when those strategies are far better than the ones tagged as “rational”.

Many years ago a simple solution crossed my mind after reading for the first time about this dilemma. The main idea was simple: The classic “solution” has a good point (the “nested thoughts”), and a crucial error (the real target: “earning money” is forgotten, and replaced by a surrogate one: earning more money than the opponent).

So I used a probabilistic approach. We start with “a priori” distribution on the “decision space” for the opponent decision, we compute the reward for every possible decision taking into account the “a priori” distribution… and then, we construct a new distribution based on the computed rewards. As you can imagine, we need to do this iteratively until the distribution converges.

If you’ve payed attention, you’ll notice that there are some loose ends:

- Will affect the chosen “a priori” distribution to the final solution?

- It’s almost obvious that we have to use a monotonous growing function over the rewards to construct the next distribution, but… there are a lot of functions, which one?

Fortunately, the “a priori” distribution doesn’t matter… (with a few exceptions), nor does the function! My exposition isn’t rigorous at all, but is supported by “empirical” data.

The only problematic distributions are the ones where the probabilities are concentrated on the lowest possible values (in our case, when only and have probabilities greater than zero).

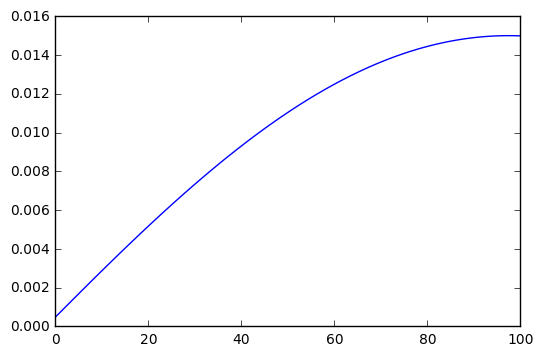

I started with the function , and tried it with many random “a priori” distributions, obtaining the same final solution every time:

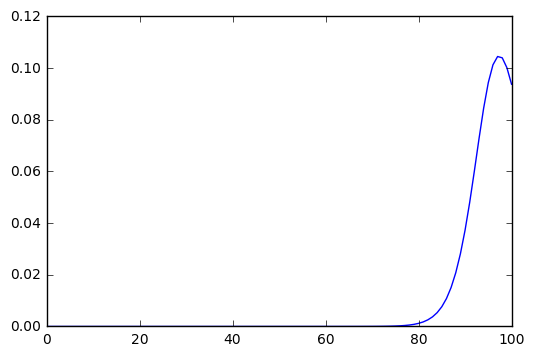

In this solution, the best options are and as the baggage prices. If we choose a higher degree polynomial the best options will change, but not much, let’s see what happens with , in this case the best option is to pick as the baggage price:

The distribution changes very smoothly respect to the polynomial exponent (this is why I’ve chosen a “big” exponent). We have a soft change, but in any case, a significant change. This leads us to the question of how to choose the function to transform the reward into a probability distribution.

What seems more “rational” to me is to maximize the reward expectations, this is, approximately (but not exactly):

Where

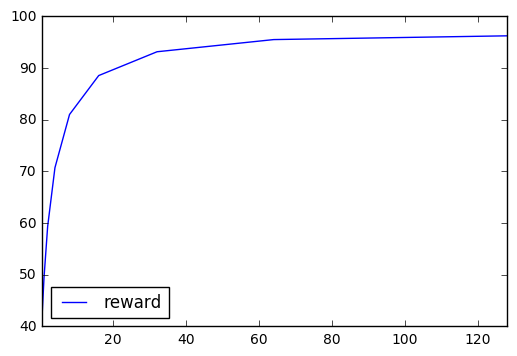

A good way to maximize the expected reward is to consider polynomials with very high exponents. Here you can see a graph of the expected reward as a function of the polynomial exponent:

It is tempting to use a more drastic approach, giving a probability of 1 to the price with the highest associated reward, and 0 to the other prices, but this approach is sensitive to the “a priori” distribution… and we don’t know anything about our opponent, so our strategy should not depend on the initial chosen distribution.

”Real world” experiment

I’m pretty sure that the exposed approach is near optimal, but can we expect a similar behavior from people? I don’t know, and I haven’t the time to conduct the required experiments.

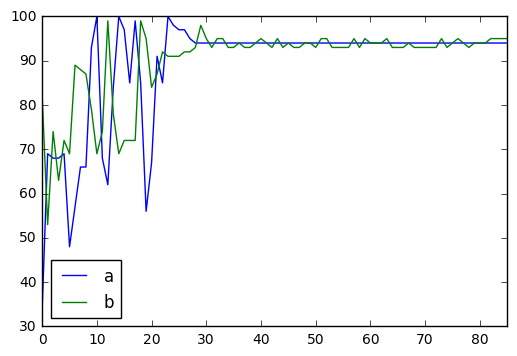

So I’ve used sklearn to implement two multilayer perceptron

instances. In first place, I’ve trained them using white noise to simulate a completely random behavior. I could use

only 4 white noise samples because using more noise samples makes impossible the training convergence.

Every playing round, the perceptrons receive the results from the previous round and use them to decide which is their next movement. The first round the perceptrons receive white noise because there is no previous historical data.

We generate new samples every round, but every “player” keeps a completely subjective view of the world (the players don’t learn from the errors of the other players).

I didn’t find a way to generate training samples completely decoupled from my first intuition. So, to reduce coupling, every player only learns part of the available info each round (if the player proposed the lowest number p, then it learns the associated rewards of the prices greater than p, and the associated rewards of the prices lesser than p otherwise).

The results are the following:

As you can see, the perceptrons proposed prices converge to , which is similar to our previous values.

A more interesting experiment might be training perceptrons to learn the best strategy depending on rather than depending on past movements (because depending on past movements only has sense when your opponent is always the same). Anyway, this is work for another article.

UPDATE: I’ve found these two interesting articles deepening into the exposed ideas, but with much more detail and rigour: